Classical and Special Relativity

Classical Relativity

Frames of Reference

An inertial frame of reference is a snapshot of a part of spacetime, which is all travelling at a constant velocity.

Galilean Invariance

Galilean invariance states that the laws of physics are the same for all inertial frames of reference. For example, doing an experiment on a vehicle moving at a constant speed will yield the same results as doing it on stationary land.

Classical Relativity

In classical relativity, velocities can be added together to get the velocity that an object appears to be moving relative to an observer.

Special Relativity

Einstein's Postulates

Einstein made two postulates when thinking about relativity, building off classical relativity:

- The laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames.

- The speed of light in a perfect vacuum is the same for all observers.

Following these postulates, some very strange properties of space and time are observed. As an object's velocity approaches the speed of light, the length of the space itself contracts in the direction the object moving, and the object will appear to pass slower through time. These new laws are now known as a part of special relativity.

The Light Clock

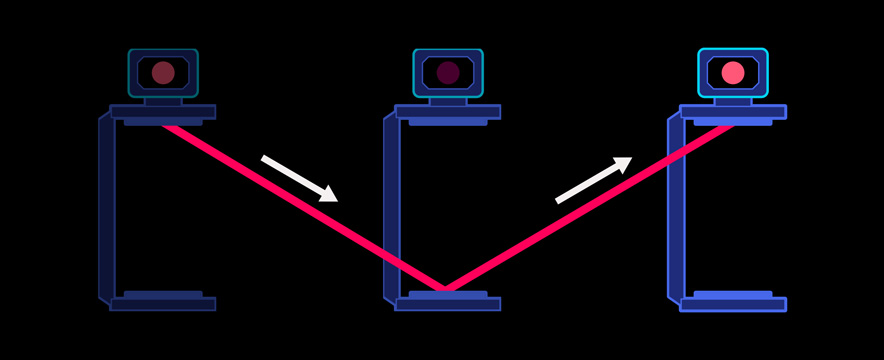

Einstein considered a thought experiment called the light clock.

Consider two perfect mirrors facing perfectly opposite each other, so that a short pulse of light travelling perpendicularly in between them would be trapped forever bouncing back and forth. When stationary, the light would bounce off a mirror at a steady rhythm.

If we start moving this contraption horizontally, then the distance the light would cover from our frame of reference would be in a triangular wave shape, as shown below. However, the light now has to cover a further distance. We cannot add on velocity if we follow postulate 2, therefore by the equation

Time Dilation

But how can the time taken increase if light is still travelling at the same speed? The actual rate of time progression would have to change - which sounds very strange, but is actually what happens. A moving clock will appear to be running slower for a stationary observer. This process is called time dilation.

The frame you are observing from is not moving relative to you, and the time you observe would be normal time. The time you observe in a frame travelling relative to you would be the dilated time.

Time Dilation Formula

is the dilated time, in seconds. is the normal time, in seconds. is the velocity of the moving object, in metres per second. is the speed of light constant, in metres per second.

A person on a rocket observes 30 seconds. The rocket travels at

ms-1 as viewed from Earth. What time is observed on the rocket's clock as viewed from Earth?

Coefficient Notation

Often when expressing a certain proportion of the speed of light, it would be notated by a number multiplied by

For example, half of the speed of light would be

Lorentz Contraction

A moving object is observed to be shorter than it actually is, for the same reason why time is observed to pass slower as well. The formula for calculating contraction is very similar, however the contracted length gets smaller instead of greater like dilated time.

Contraction Formula

is the contracted length, in metres. is the normal length, in metres. is the velocity of the moving object, in metres per second. is the speed of light constant, in metres per second.

Proof of Special Relativity

Muons are high-energy lepton particles similar to an electron. They are formed in the Earth's upper atmosphere, at an altitude of about

Using Classical Physics

According to classical physics (physics pre-dating quantum and relativistic physics), the muon should decay before it reaches the ground. The probability of a muon reaching the Earth's surface without travelling faster than the speed of light is about zero.

Using Special Relativity

Ground observer's perspective

An observer on the ground would observe dilated time when watching the muon, which would give it enough time to reach the ground without decaying.

Muon's perspective

The muon would observe the distance to the Earth's surface contract, so that it needs to cover less distance in order to reach the surface without decaying.